‘A resident artist is a maker who’s temporarily relating to another place,’ Verrijt says, as he begins talking about his residency at United Cowboys — an art house and dance performance company.

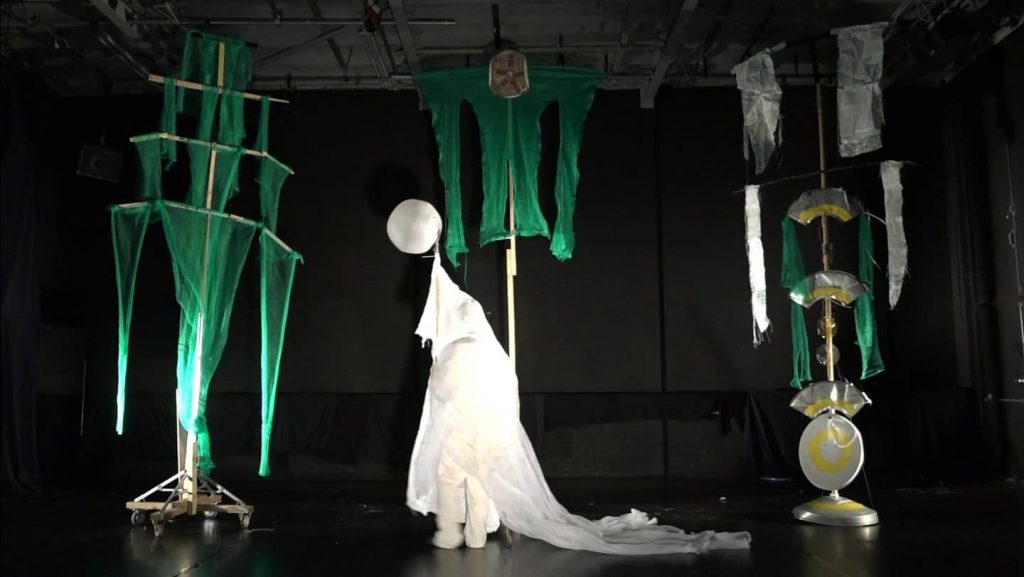

He wants to connect this interview with what is happening within the four walls of the Art House. We’re sitting on small wooden bleachers in a two-storied, square space that is lit by overhead theatre spotlights. I’m seated directly under these spotlights when I’m offered a cup of tea. From our bleacher vantage point, we’re looking out onto a dark theatre floor with forms that stretch several metres high. Owing to their physicality and materiality, as well as the inspiration with which Verrijt talks about them, the objects soon constitute the audience for our conversation. Some are as tall as the space itself; others are short and compact. These figures are made of building materials, wooden sticks, cardboard and pieces of foam. Colourful fragments of canvas give off an impression of sailing masts, but also of ritualistic objects. To better understand Verrijt’s relationship to these sculptures, I ask if they have a name. ‘They do not have a name because I begin from a kind of liminal space. If they were named, they would become a singular thing, imbued with a history. That would obstruct their openness; the very thing I find so intriguing. It’s up to you to fill in the blanks,’ muses Verrijt.

The objects before us are both artworks as well as subjects of the films that Verrijt is showing. He alternately refers to these objects as sculptures, architectonic vehicles, characters and entities. They are also collages of discarded materials that were sourced in Eindhoven. On Friday a city car will come to pick up the cardboard, so Verrijt does a last round before it’s hauled away. The sailcloth, sticks, styrofoam, wood and steel will all take on another life in Verrijt’s studio. ‘Collecting and bringing materials together creates an ecosystem of items that would otherwise be overlooked. What’s more, these materials say something about the surroundings,’ remarks Verrijt. Across the bleachers, colourful sketches lie scattered of various sculptures that may or may not be present in their full form. ‘I sometimes draw them ten times,’ notes Verrijt. He sketches the sculptures to forge a relationship between the different entities; his way of trying to internalise their form and function.

Verrijt, however, continues to work on his sculptures; constructing new components and breaking off others. Some components remain, others fall away. No two performances are alike, and no form is sacred. This interplay of construction and deconstruction illustrates his emphasis on the fluid nature of his sculptures. Verrijt creates an organic collective that —both in the literal and figurative sense — is in constant motion. He points to the underside of his sculptures. Their mobility is not merely conceptual, it’s also literal. Each figure is mounted on wheels and can be manned for operation. ‘They’re also costumes’ divulges Verrijt. But these costumes are far from comfortable and their wearability is limited. Comfort is not the goal, however, and these constraints produce exciting effects. ‘These are costumes for an impossible dance,’ observes Verrijt. With this dance, Verrijt does not want to draw you into a story, but rather to disorient you. Here, disorientation is a critical force that exposes the patterns of a ritual. In this case, a performance ritual.

It’s not purely the work that matters; the audience, space, time and context are also important.

Verrijt’s artistic springboards are the ideas and principles of scenography, but he always moves away from the frameworks associated with stage craft. Verrijt builds the figures, sets and props, all of which he views as an immersive installation. Not only are his figures protagonists in a storyline, they’re also secondary characters in installations that interrogate theatricality. Verrijt clarifies, ‘It’s not purely the work that matters; the audience, space, time and context are also important.’ As an example, he mentions the bleachers on which we’re perched. According to Verrijt, ‘The bleachers are an orientative element that confer a certain role to the audience. A role that I want to undermine.’ Verrijt wants to explore these orientative frameworks throughout the course of his residency. ‘That’s why I’m so inspired to work for three months at United Cowboys in an actual theatre and performance space,’ he offers up, ‘Here, I have the entire theatre floor and the balconies, lights and sound at my disposal. I also have the opportunity to discuss my work with United Cowboys’ artistic directors: Maarten van der Put (concept, direction, design) and Pauline Roelants (choreographer).’ United Cowboys has a rich tradition of stretching theatrical and performative conventions.

Beyond indoor shows, his motley crew of mobile sculptures also take to the streets. Verrijt organises performances in public spaces. This itinerant band of unusual figures is sometimes likened to a funfair that roams from place to place. It reminds me of the ‘Carnivalesque’. A concept which, due to Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin, gained significance as a literary mode that had a subversive, liberating function. Exaggeration, for instance, is employed to lampoon opposites like good and evil, rich and poor. As the term implies, the cultural function of carnival is hidden within it. More than just popular entertainment, carnival parades were a way to mock the feudal and religious elite in order to address the established order. Verrijt’s mobile sculptures fulfil a similar function within the historically Catholic environment of Eindhoven. As for which contemporary societal frameworks are being addressed, Verrijt leaves that open to interpretation.

What struck me most was that, through the films, the figures elicit an affective response. The sculptures move and suggest everyday behaviour, rituals, emotions and interactions. The films portray a spectacle in which bodily excesses, egos and turmoil are magnified. ‘Film has the potential not only to document and archive, but also to manipulate,’ cautions Verrijt. Each entity receives its own role within these obstacles and possibilities. While we’re admiring the sculptural elements of the entities in the space, Verrijt uses his films to play with the narrative and affective aspects of theatre. In Verrijt’s installations, members of the public literally stand next to the sculptures, but they’re also spectators to their affect.

United Cowboys

In the heart of Eindhoven’s city centre lies the Art House, the work space of the art collective United Cowboys. The building provides space to artists for meetings, research and presentations. In the span of a few years, the Art House has grown into an international platform whose explicitly interdisciplinary approach, like the artwork of United Cowboys itself, operates at the interface of dance, performance and visual culture.

Wessel Verrijt will make a digital presentation to conclude this residency period, which will be shown from the beginning of May. On 27, 28, 29 and 30 April and 1, 2 and 3 May, there is the opportunity to pay a professional studio visit, individually or in pairs, and see the results of the residency. During these visits, we carefully observe the Covid rules. You can register via wesselverrijt@gmail.com

Author: Hannah Kalverda